In Summary...

Who requires surgery?

Recent PCL lesions if combined with peripheral ligaments. Old lesions if knee unstable or bothersome patellar pain

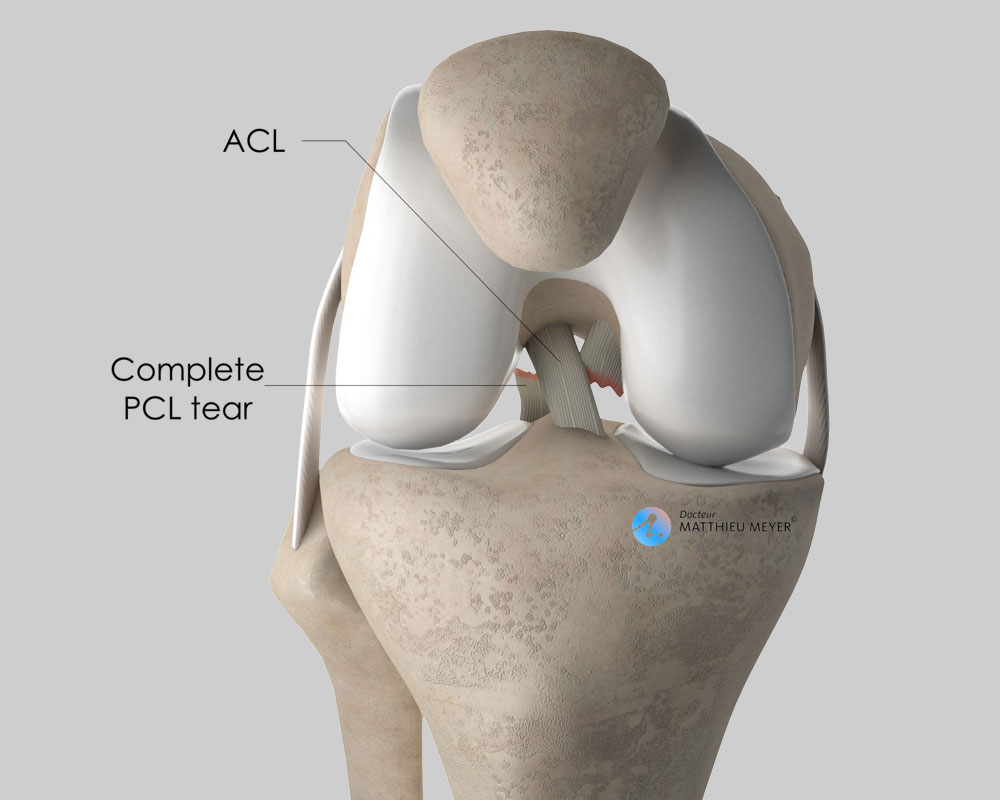

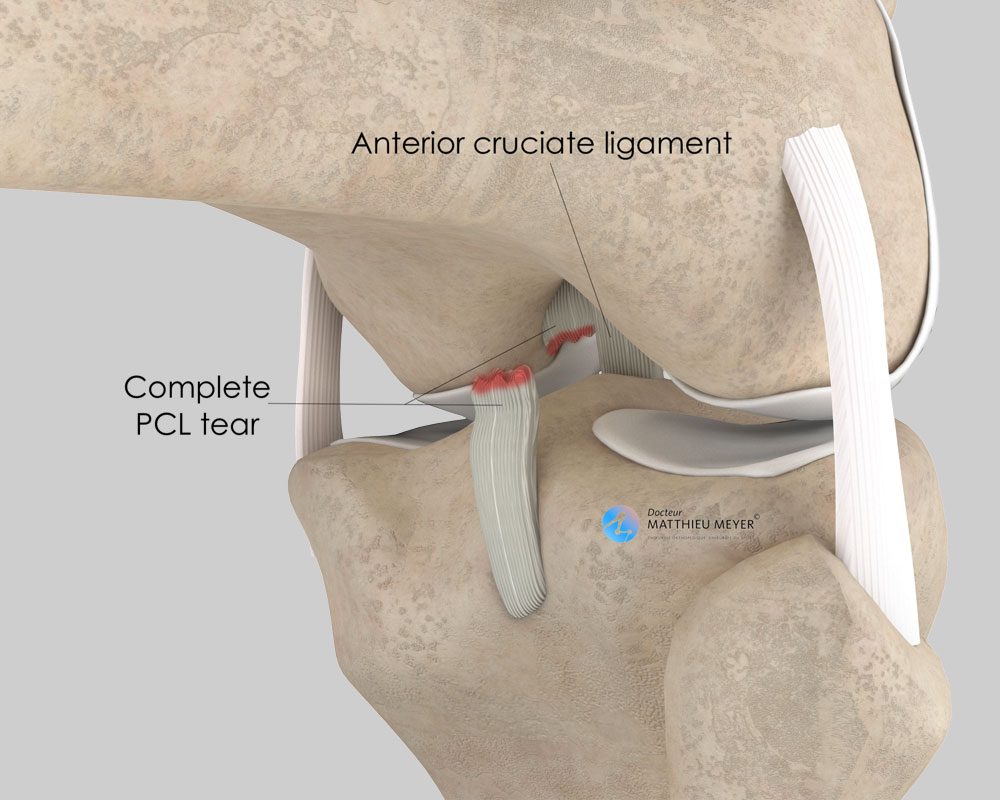

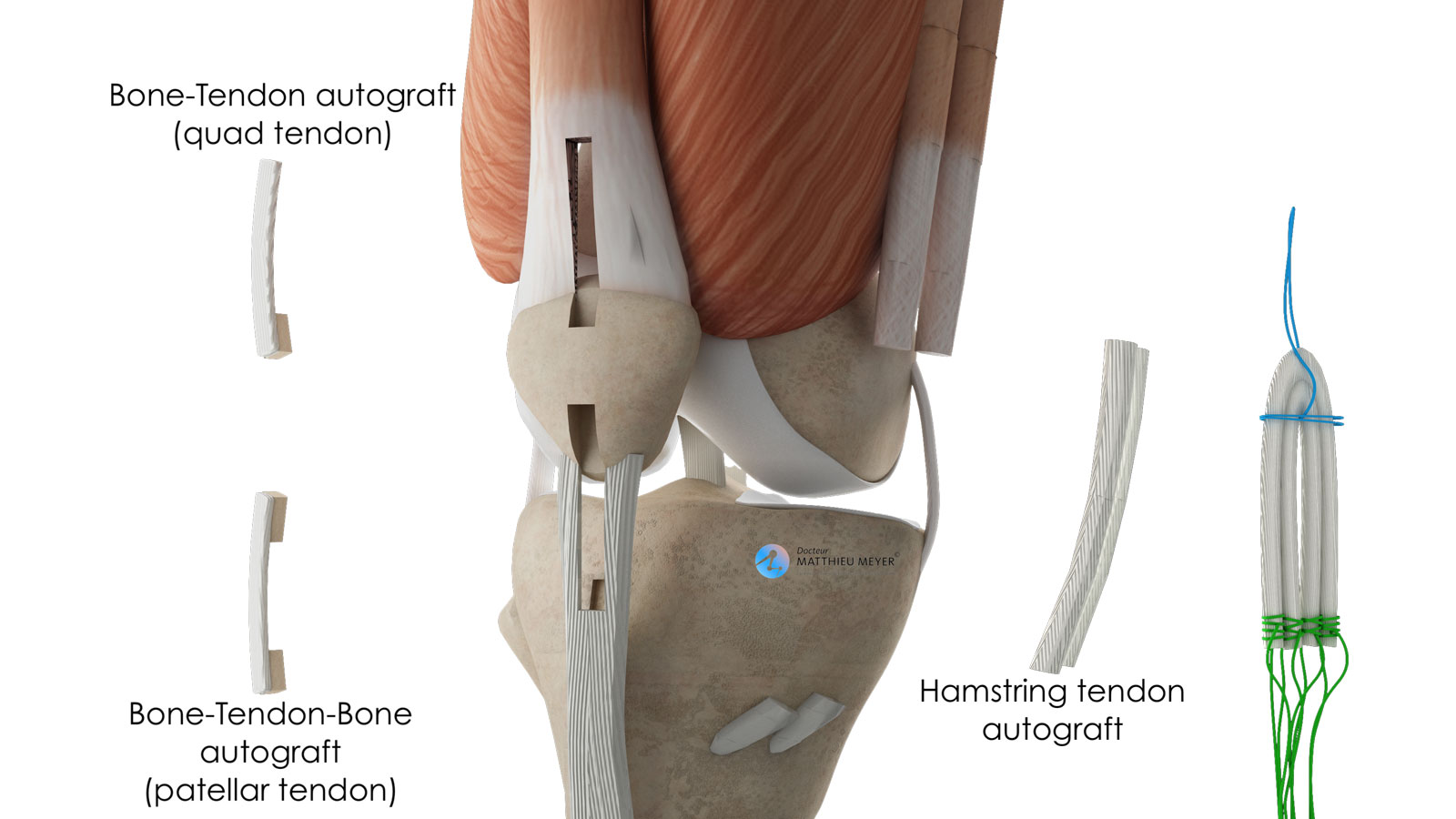

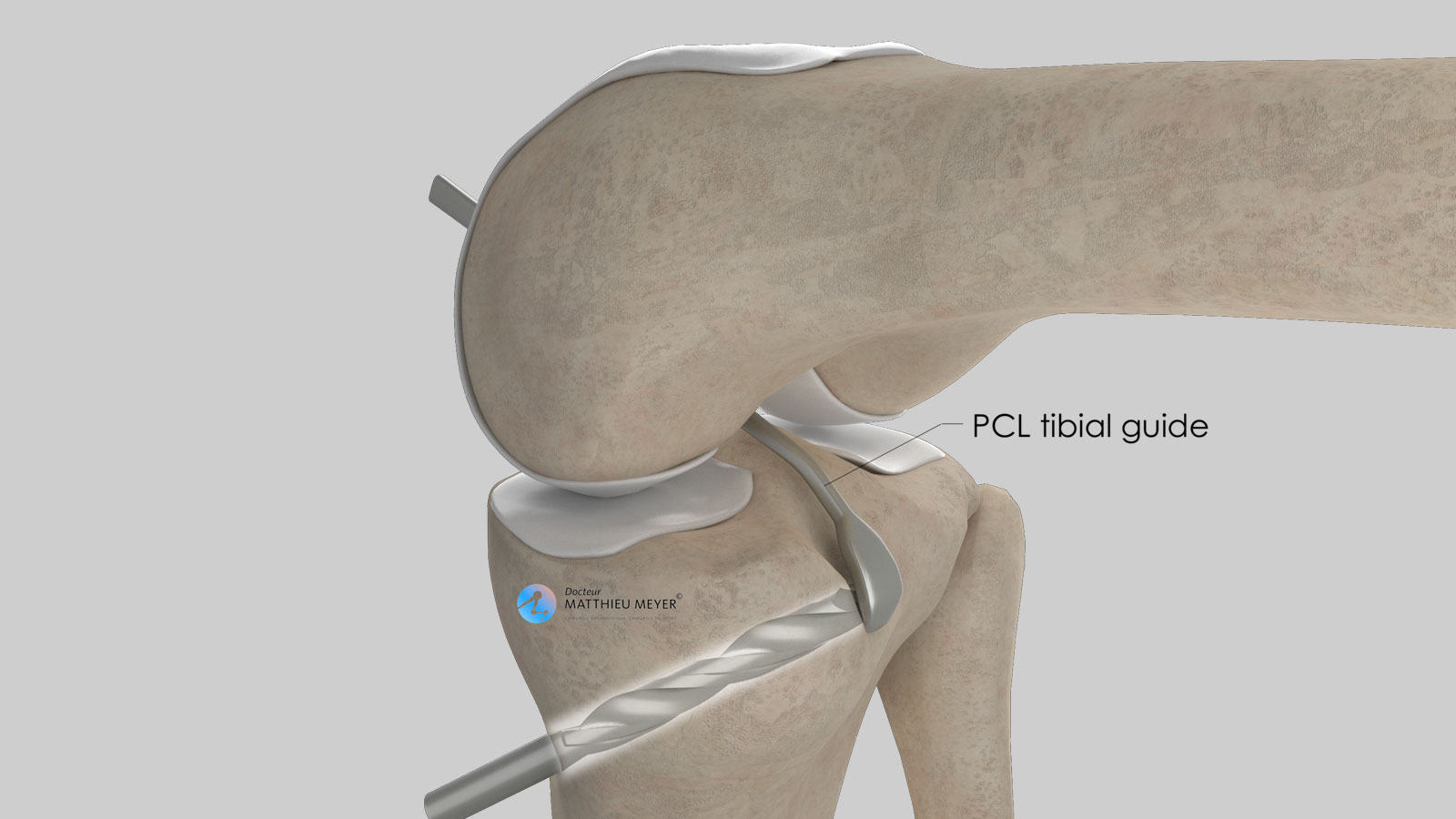

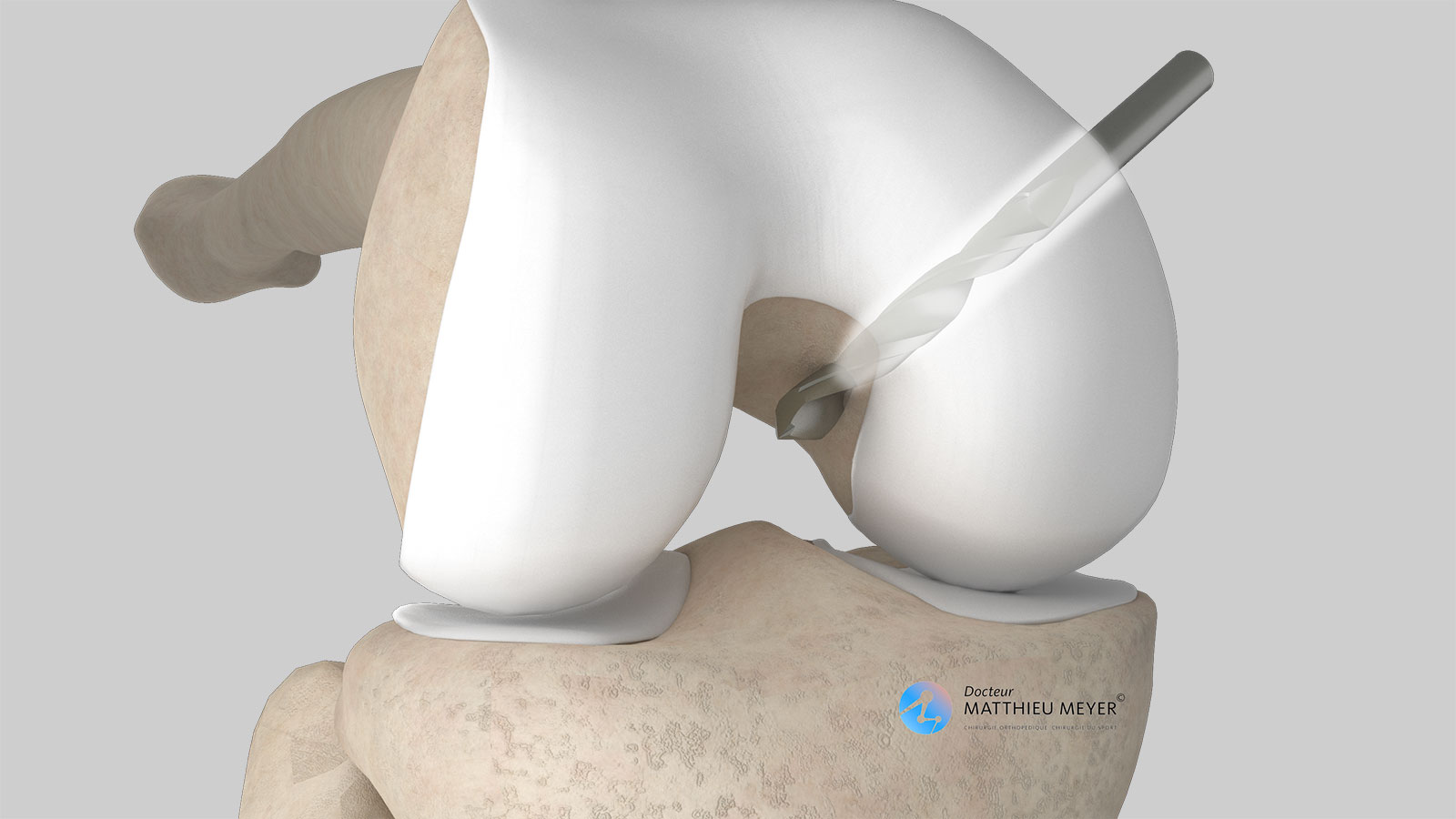

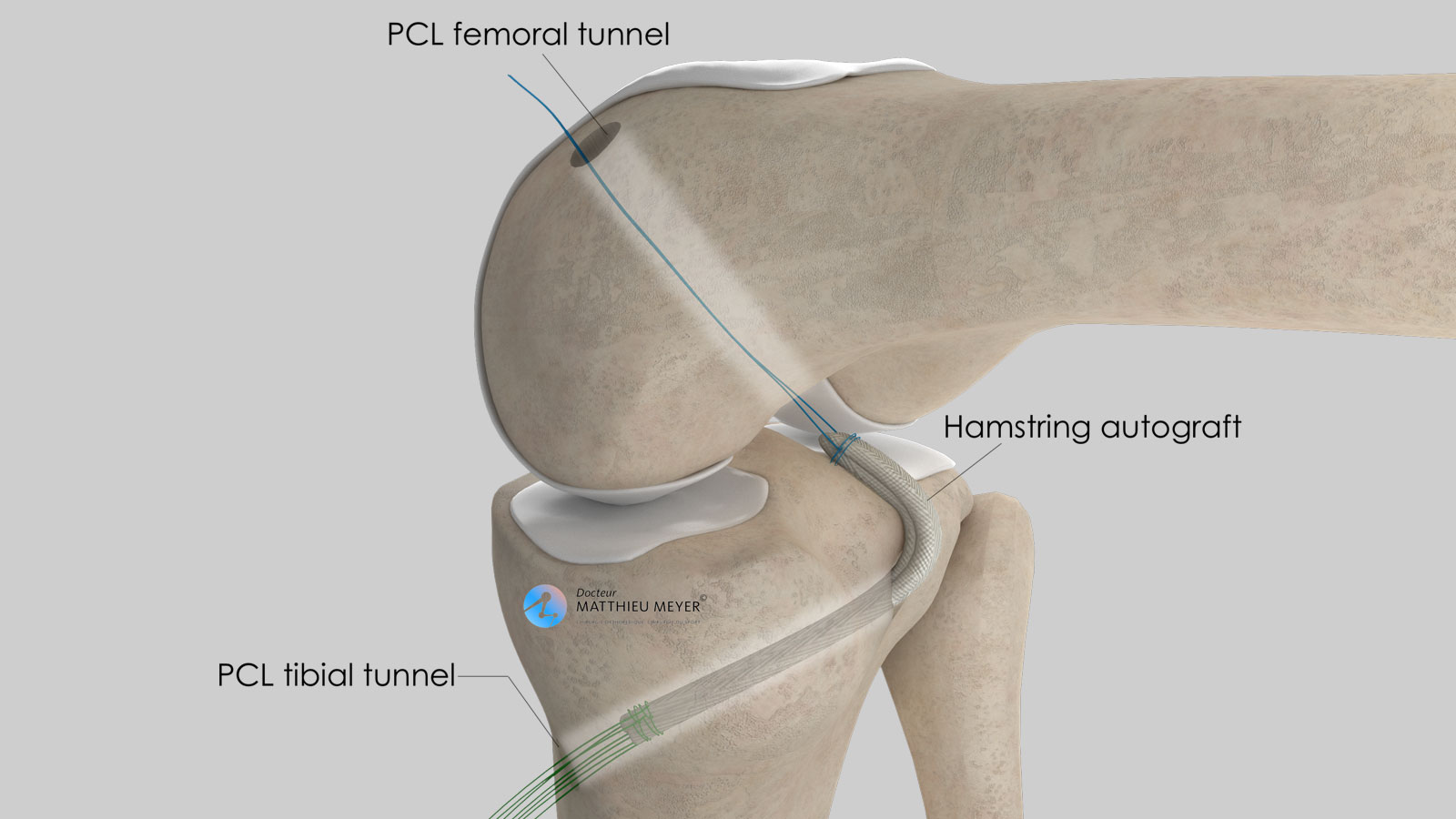

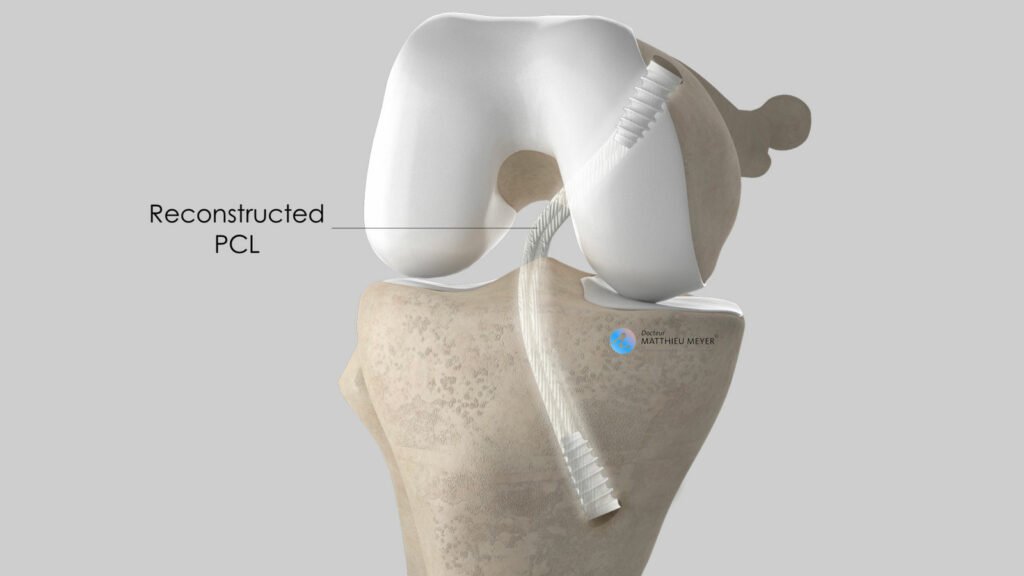

Surgical technique

Arthroscopy for PCL

Which anaesthesia?

General or regional according to the patient’s history and wishes (determined with the anaesthetist)

Duration of hospitalisation

Outpatient surgery or 1 to 2 nights at the clinic (longer in the case of damage to several ligaments)

Resumption of weight-bearing

Immediate alleviated with crutches for 3 weeks

Duration of medical leave

1 to 3 months depending on the profession

Resumption of car driving

6 weeks after the operation

Resumption of riding a motorbike

4 months after the operation

Resumption of sport

Progressive from the 3rd month after the operation and from the 9th month for pivoting sports